Indigenous Land

Contents

Introduction

Sometime in 2018, I came across the website of game designer Avery Alder. I noticed that she described where she lived as "in the Slocan Valley, in Sinixt and Ktunaxa Territory," and not as "British Columbia, Canada."

She elaborates on her motivations in a series of Tweets (on 15 September 2018):

I frequently get cited as a 'Canadian game designer', and for the record I am always bothered by that. I'm a designer on unceded Sinixt territory, and previous to moving I was a designer on unceded Squamish, Musqueam, and Tsleil-Waututh territory'

as a settler on unceded land, I do not want my work attributed to Canada, nor do I want to be involved in any assertion of its primacy over this land.

[...]

This was my first introduction to the concept of "unceded territory." Doing some searches on the Web for this term introduced me to the practice of "land acknowledgements." These are both connected to the project of decolonization, which I now realize I know woefully little about.

As I learn more about this complex relationship between land and people, I want to collect some of the resources I find and share them on this page.

Unceded Territory

In North America, colonial powers entered into numerous treaties with native peoples to acquire land in exchange for goods and currency. In this way huge portions of North America, via convoluted "chains of title," came to be claimed by what are now Canada and the United States. [2] For much of the land in these two states, the government can point to a particular legal document which enacted the transfer in ownership. But for large expanses of the land, Canada and the US do not possess even the most tenuous legal claim. This land is considered "unceded."

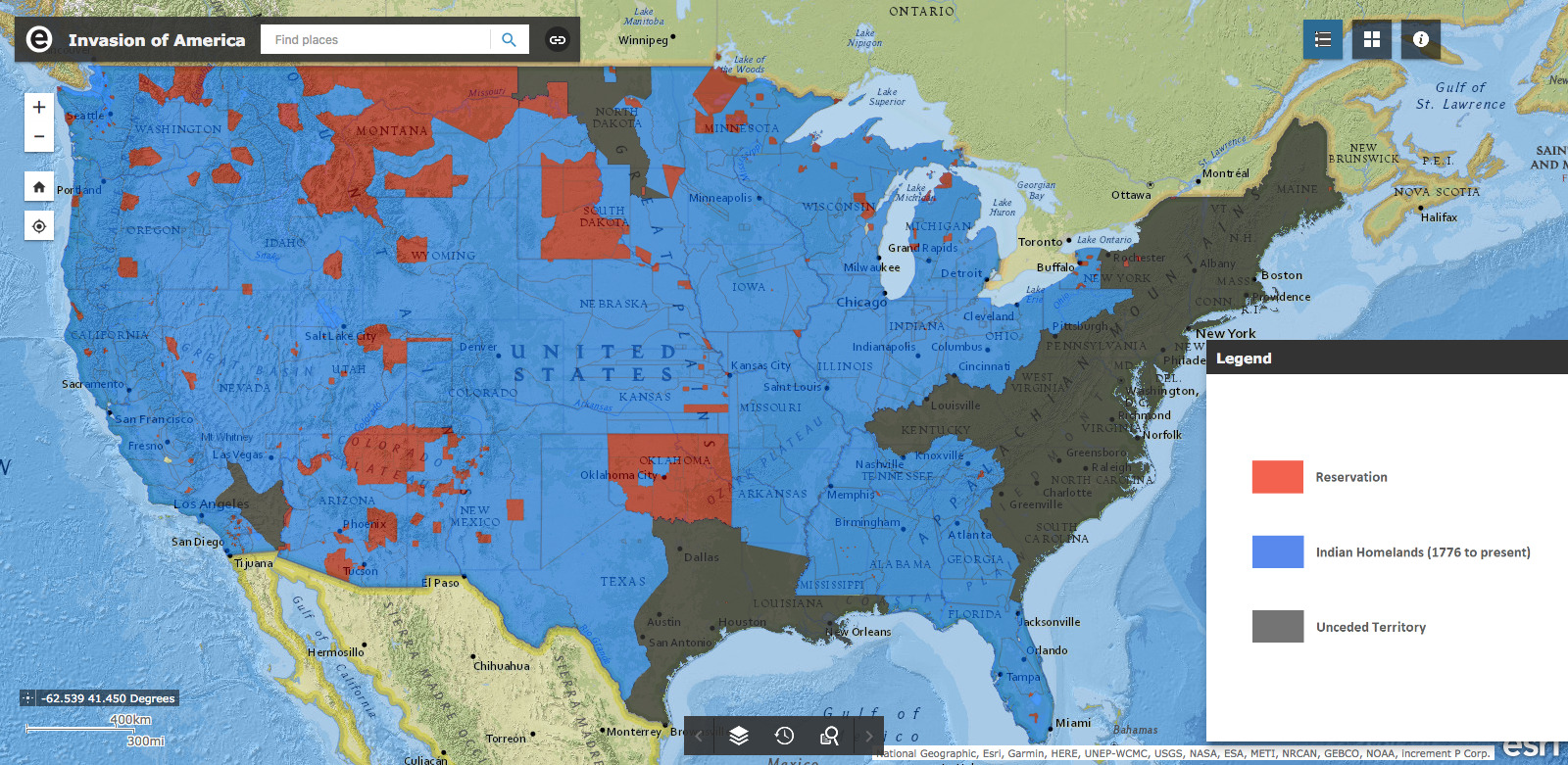

In the United States, the most obvious tract of unceded territory is the land around the original 13 British colonies on the Eastern seaboard. Another notable piece is eastern Texas, which was "[s]eized by force of arms by the Republic of Texas and the United States in the nineteenth century." [3]

In Canada up until 1975, most of British Columbia, Québec, Yukon, and Nunavut were unceded territory. Since then, there have been some new treaties seeking to fill in these gaps, such as the 1975 James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement and the 1993 Nunavut Land Claims Agreement. Below is where things stood before 1975. The white areas of the map were those not covered by any treaty. [4]

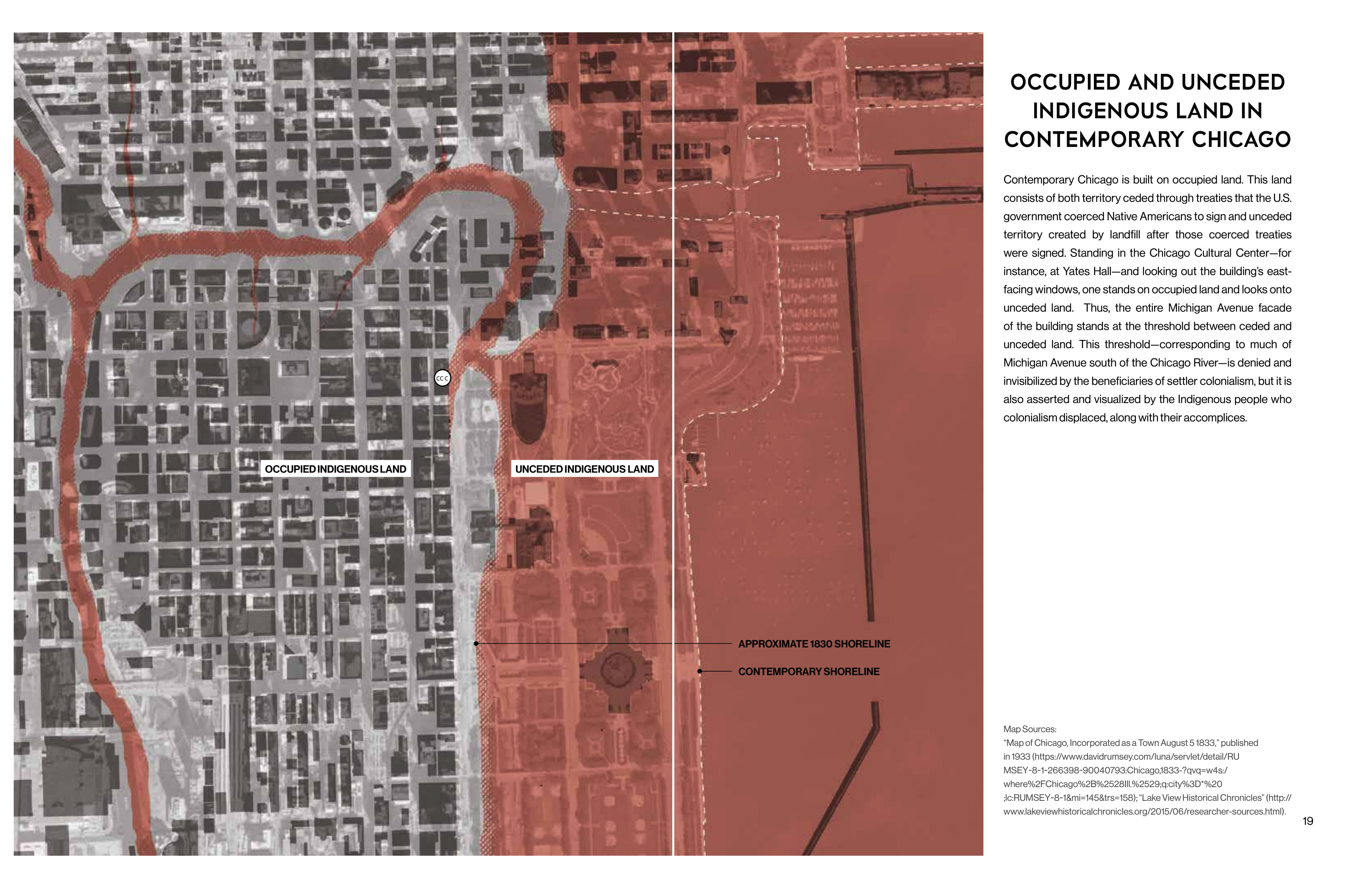

As of 2019, I live in Chicago, Illinois. As best I can tell, the land underneath the city center was ceded to the United States in the Treaty of Greenville in 1795. The counterparty to the treaty was the Western Confederacy, a confederacy of Native American nations in the Great Lakes region. Among other terms, this treaty ceded six square miles around the mouth of the Chicago River at Lake Michigan, an important portage between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River.

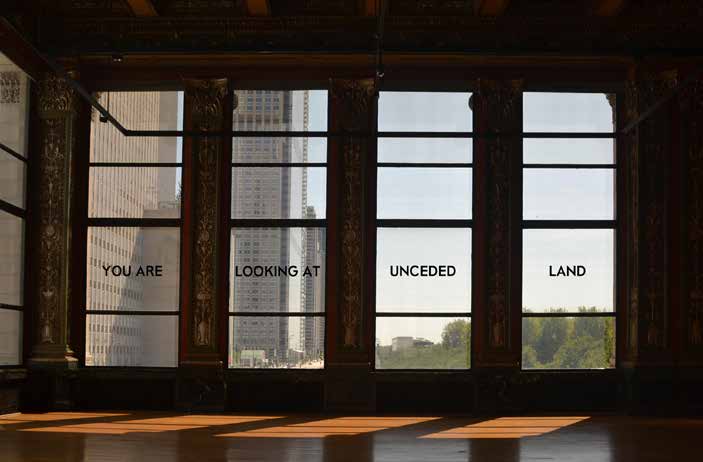

The shoreline with Lake Michigan has been pushed back since the Treaty of Greenville, the lake filled in with debris from the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 and by later efforts in order to create more land. As a result, much of the coastal land in this area is not part of any treaty. Here is a diagram from Mapping Chicagou/Chicago illustrating this. The red areas show the original waterways. [1]

Because this "new" land was never covered by any treaty, the authors characterize it as unceded. Below is a photo of an installation piece at the Chicago Cultural Center's 2019 Architecture Biennial (also taken from Mapping Chicagou/Chicago). These windows face east over Michigan Avenue, a street which originally ran along the lake shore.

| [1] | Mapping Chicagou/Chicago: A Living Atlas. Settler Colonial City Project, 2019. Available online here. ISBN 978-0-578-56262-9 |

| [2] | I have focused on Canada and the United States here. In the future I may try to learn more about the colonial history of Meso/Central America and the Carribean, as well as South America. |

| [3] | This image is from the map accompanying Claudio Saunt's book West of the Revolution. See United States section for more information. |

| [4] | This map is from the RCAANC / CIRNAC. See Canada section for more information. |

Land Acknowledgement

A land acknowledgement (as it is sometimes called) is a public statement acknowledging the original habitants of the physical space that the audience now occupies. It acknowledges the existence and legitimacy of the original peoples and that those gathered there are guests. It acknowledges the history of colonialism and displacement of indigenous peoples.

They are usually made at public events—like lectures, arts performances, sports matches—and by public institutions that occupy space such as schools and universities.

When I first learned of the concept, it seemed to be a practice that had only gained a foothold in Canada (and possibly other "progressive" former British colonies like Australia and New Zealand) and not in my native United States. But since I've become aware of the idea, I have stumbled on a couple land acknowledgements here.

Chicago Cultural Center

The Settler Colonial City Project (SCCP), [5] in partnership with the American Indian Center of Chicago (AIC), [6] were contributors to the 2019 Chicago Architecture Biennial held at the Chicago Cultural Center. The SCCP was commissioned to attempt the insurmountable task of "decolonizing the Chicago Cultural Center." As part of this project the AIC drafted a land acknowledgement. The preface to the acknowledge provides some context for this type of statement: [7]

In recent years it has become a trend to acknowledge the traditional homelands of the Indigenous peoples of a particular area through a land acknowledgement. This type of activity is designed to bring more awareness and understanding of the history of Indigenous people and their territories. But a land acknowledgement should also be more than that; it should be a call to rethink one's own relationship with the environment and the histories of all peoples. [...]

The acknowledgement itself, displayed at the entrance of the Chicago Cultural Center, read:

Chicago is part of the traditional homelands of the Council of the Three Fires: the Odawa, Ojibwe, and the Potawatomi nations. Many other tribes—such as the Miami, Ho-Chunk, Sac, and Fox—also called this area home. Located at the intersection of several great waterways, the land naturally became a site of travel and healing for many tribes. Today, Chicago is still a place that calls people from diverse backgrounds to live and gather. American Indians continue to live in the region, and Chicago is home to the country's third-largest urban American Indian community, which still practices its heritage and traditions, including care for the land and waterways. Despite the numerous changes the city has experienced, its American Indian and architecture communities both see the importance of the land and of this place, which has always been hospitable to many difference backgrounds and perspectives.

| [5] | The Settler Colonial City Project is a research collective which explores cities as sites of ongoing settler colonialism and Indigenous resistance. |

| [6] | The American Indian Center of Chicago is cultural and community center serving Native Americans in the Chicago area. |

| [7] | Decolonizing the Chicago Cultural Center. Settler Colonial City Project, 2019. Available online here. ISBN 978-0-578-56876-8 |

University of Illinois

During the 2019 season of the Krannert Center for the Performing Arts, [8] the programs handed out at performances included a land acknowledgement. The text from the program of a play I attended reads:

The University of Illinois System carries out its mission in its namesake state, which includes the traditional territory of the Peoria, Kaskaskia, Piankashaw, Wea, Miami, Mascoutin, Odawa, Sauk, Mesquaki, Kickapoo, Potawatomi, Ojibwe, Menominee, Ho-Chunk, and Chickasaw Nations. These lands continue to carry stories of these Nations and their struggles for survival and identity.

As a land-grant institution, the University of Illinois has a particular responsibility to acknowledge the peoples of these lands, as well as the histories of dispossession that have allowed for the growth of this institution for the past 150 years. We are also obligated to reflect on and actively address these histories and the role that this university has played in shaping them. This acknowledgement and the centering of Native peoples is a start ass we move forward for the next 150 years.

Krannert Center affirms the commitment by the university to move beyond these statements, toward building deeper relationships and taking actions that uphold and preserve Indigenous rights and cultural equity.

[...]

Some context for the University's acknowledgement is provided on its website. The text of the acknowledgement itself is also published on the website for the Office of the Chancellor.

| [8] | Krannert Center is located on the campus of the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. It is owned and administered by the University. |

Canadian Association of University Teachers

The Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT) has a published a guide on land acknowledgements for Canadian universities along with recommended text.

The acknowledgement for the University of Toronto (provided by the University itself) reads:

1/ We [I] would like to begin by acknowledging that the land on which we gather is the traditional territory of the Wendat, the Anishnaabeg, Haudenosaunee, Métis, and the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation.

2/ I (we) wish to acknowledge this land on which the University of Toronto operates. For thousands of years it has been the traditional land of the Huron-Wendat, the Seneca, and most recently, the Mississaugas of the Credit River. Today, this meeting place is still the home to many Indigenous people from across Turtle Island [9] and we are grateful to have the opportunity to work on this land.

| [9] | Turtle Island is a name for the North American continent originally drawn from Lenape folklore, per Wikipedia. |

Maps and Treaties

Canada

The Relations Couronne-Autochtones et Affaires du Nord Canada (RCAANC) / Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) department of the Canadian government has published a series of maps of Canadian territory from 1871 up until 1975.

Native Land Digital, a Canadian non-profit group, has published an interactive map showing the lands of indigenous peoples as well as the extent of cessions under various treaties. The map covers most North America, not Canada alone.

United States

To accompany Claudio Saunt's book West of the Revolution, [10] an interactive map of land cessions to the United States was produced, hosted online here. [11] The map shows the parcel of land covered in each of the cessions along with links to text of the treaties. It also shows the boundaries of recognized Native American territory today.

The information on the cessions comes from two books. First of which is the Eighteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, produced in 1896–97. [12] The second part of the book contains a section "Indian Land Cessions in the United States" compiled by Charles C. Royce. There are extensive tables containing dates, signatories, and a brief description of the treaties between between the United States and Native nations and confederations. It is available to read on Archive.org.

The second book is Indian Affairs: Laws And Treaties, compiled in 1902 by Charles J. Kappler, Clerk to the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs. [13] This contains the full text of the treaties. It is available to read at HathiTrust.org.

I also found a map of "Indian land areas judicially established". [14] I believe it was produced at the direction of the Indian Claims Commission before its closing in 1978. The map contains a note that says:

This map portrays the results of cases before the U.S. Indian Claims Commission or U.S. Court of Claims in which an American Indian tribe proved its original tribal occupancy of a tract within the continental United States.

| [10] | Saunt, Claudio. West of the Revolution: An Uncommon History of 1776. W. W. Norton & Company, 2014. |

| [11] | The map URL, invasionofamerica.ehistory.org, redirects to a page at the arcgis.com domain, http://usg.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=eb6ca76e008543a89349ff2517db47e6. I suspect that one of these links will break someday and this painstakingly detailed ArcGIS map will become inacessible. |

| [12] | Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Ed. by J. W. Powell, vol. 18. Government Printing Office, 1899. |

| [13] | Indian Affairs: Laws And Treaties. Ed. by Charles J. Kappler, 5 vols. Government Printing Office, 1904. |

| [14] | The digital object identifier (DOI) link with more metadata is https://doi.org/10.3133/70114965. |